Search

2009-07-31

Hayao Miyazaki and John Lasseter Press Conference

Fatherhood and the Family Crown

Question: You mentioned Tales from Earthsea. Miyazaki-san, since your son directed that film, and it occurred before Ponyo, what has he been doing since in carrying on the family tradition? And Mr. Lasseter, I didn’t realize you had already prepared a version of that. I thought there was a rights issue with the Ursula Le Guin estate. What is the status of that?

Lasseter: We’re just kinda wading through that, and there’s a time limit. It will be released at some point.

Question: But the version is ready to go?

Lasseter: It’s ready.

Miyazaki: My son is now in childrearing.

Lasseter: Which is very important to Miyazaki-san.

Miyazaki: That’s a very important process.

Question: Is there anything more to be said about your son’s interest in animation?

Miyazaki: It’s a difficult question, but I don’t see myself creating a directors dynasty, unless he can crawl up to be a director on his own. It’s up to him. The first hurdle right now is raising his children.

This is a very sensitive subject, as you can see from Lasseter's efforts to deflect the issue (that's what friends do, after all). Besides, Hayao Miyazaki is here to discuss his latest film, Ponyo, not to be caught up in the complicated relationship with his son, Goro. But I am very impressed with his answer. Read in light of news about Goro's Studio Ghibli film short, we have been given a new insight into the inner workings of the studio.

At this point, I think it's safe to say that Goro-san will not be directing any feature film at Ghibli in the immediate future. One thing Gedo Senki revealed, painfully, I think, was his complete inexperience as a filmmaker. That was not only his first movie as director, it was his first movie. And I think that was somewhat obvious. Japanese audiences turned out for Earthsea, making it the year's highest-grossing domestic movie, but that was largely due to loyalty for Father Miyazaki. The backlash against the son, both for his film and his remarks about his father, was very real, and I don't think that's going to be easily forgotten.

Goro has lost the public goodwill, and he will need to win them back. He will have to work and struggle to earn his father's throne and become the heir to Studio Ghibli. That's what the issue is really all about. In retrospect, I believe it was a mistake for Toshio Suzuki to place Goro in the director's chair so soon, all but declaring him the studio's heir apparant. Goro needs time to grow, to learn, to develop a style, to master the skills of a filmmaker, director, and leader.

Toshio Suzuki's business sense has always been spectacular, and his influence on the direction and style of Ghibli's movies is far greater than most Westerners realize. He knows how to push Miyazaki's buttons. He knows how to get things done. There literally wouldn't be a Studio Ghibli without him. And he may yet be proven right by choosing Goro; he may yet be vindicated. For the hope of the studio, I hope this is so. I think he just moved too fast, too soon. Perhaps everyone was blinded by the family name without careful consideration. Isao Takahata's calm teaching at the end of My Neighbors the Yamadas echoes in the hallways: don't overdo it.

Now it appears that Goro will have his apprenticeship period, with the film short being the latest example. There was also an exhibition at the Ghibli Museum where he storyboarded and assembled a story based on a famous Japanese poet. It was not an actual movie project, but much closer to a class assignment at film school. That is precisely the direction he needs to take. And it's very clear that Father Miyazaki's wishes shall be honored. Perhaps this is a period of adjustment for him, as well.

I have no doubt that, on some level, Father Miyazaki is happy to have Son Goro continue the family tradition. After all, Goro was the director of the Ghibli Museum since its founding, and his wife also works at the studio. The younger son, Keisuke Miyazaki, created the woodcut carving of a violin craftsman for Mimi wo Sumaseba. And Akemi Ota Miyazaki, the wife and mother, haunts her husband's work, like Julietta Massina and Frederico Fellini.

I'll bet you weren't expecting this kind of family drama, huh? You just wanted to watch movies about Totoros and goldfish. Such are the lives of great artists.

John Lasseter - Translating Ponyo into English

One of the biggest challenges in taking and creating the English-language versions of Miyazaki-san’s films… This is the third, no, the fourth one I’ve really worked on: Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Tales from Earthsea and now Ponyo. I don’t ever want the English version to change anything in Miyazaki-san’s story. The goal is to make the film for American audiences and just for the language to be very natural. You don’t think of this as being a dubbed Japanese film. That’s not what we want. We want everyone to just get swept away with the story.

However, there are sometimes things that Japanese audiences will understand visually that American audiences won’t. In those cases, what I always strive to do is to make sure the American audiences will be at the exact same level of understanding at that one time in the movie as a Japanese audience would be. An obvious example of that is back on Spirited Away, when the main character is walking and when she’s exploring the village, she looks at this building. All Japanese members of the audience would look at it and know right away it’s a bathhouse, but no one in this country would know that’s a bathhouse. So you just add a little line of “Oh, it’s a bathhouse.” It’s little tricks like that. That’s not changing anything. It’s just keeping them understanding.

One of the things to understand is in Japan, especially with Hayao Miyazaki, he always records the original dialogue after he’s finished the animation, which is different from what we do in this country. We always record the dialogue before we do the animation. So the lip-sync is somewhat on the rough side anyway. It helps us fit the words in there. But we try very hard working with the actors to get the lines of dialogue to fit with the right mouth movement, because you don’t want to have someone sit there talking and nothing’s coming out or saying a whole bunch of words, but there’s no mouth movement. You want to try and fit it in there.

The goal is the lights dim, the audience in America is taken away, is swept away by this beautiful story and visuals and the characterizations. So we work really hard to make it seem as natural as possible.

Goro Miyazaki's New Studio Ghibl Film

Goro Miyazaki is back, and you may be surprised. Comic Natalie reports that Goro has directed an animation short for Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shinbun. Studio Ghibli has created a number of commercials for the newspaper, which can be seen on the the Ghibli Short Short DVD. This latest short will debut August 1 on Japan TV.

It's well known that Goro-san was working on his next directoral film, but I'm sure most of us assumed it would be the formal follow-up to Tales From Earthsea. This move is a surprising development, and, frankly, a welcome one. The young Miyazaki needs to pay his dues properly, instead of merely being dropped into the director's chair like a prince. He needs to learn the skills and develop his own style. Gedo Senki made this all too clear. His role in the future of Ghibli will be crucial, so he needs to get this right.

It helps tremendously that Studio Ghibli does so well with their shorts. Too few Westerners are aware of this side to the studio, which is often more adventurous and experimental than the feature films.

One more important piece of news: Hayao Miyazaki was in charge of production for this short. This is a remarkable development, given the strained relationship between father and son, and again strongly suggests that Goro is being properly tutored by the old masters. Father Miyazaki will not grant a family dynasty for the studio; son Goro will have to earn his father's crown the old-fashioned way. I sincerely hope he directs a few more short films. The experience will do him good.

In case you're wondering, the visual style of this ad is inspired by Japanese manga artist Sugiura Shigura. Isao Takahata paid homage to him in Pom Poko, as I'm sure you can see by that first screenshot. This style is very classical, in keeping with Ghibli's tradition of nostalgia; it also continues the hand-drawn style of Ponyo, rejecting any "computer" look. I'm also reminded of the silent-era cartoons from the Fleischer Bros, which were a great influence on Japanese animators, and Father Miyazaki in particular. I'm really looking forward to seeing this in motion. It's going to be terrific and it may turn a few heads.

It's the hardest thing in the world to follow in the footsteps of a famous parent. For Goro Miyazaki, it's doubly difficult, as both parents were groundbreaking animators, and Hayao Miyazaki has become the biggest filmmaker in the world. Those are very long shadows. But this short demonstrates that he's taking the right steps, making the right moves, and hopefully learning the right lessons. The son is too smart to have Gedo Senki, that childish tantrum of a picture, wrapped around his neck. I'm counting this latest short film as a win for Goro Miyazaki.

Get your Tivo's ready and keep your eyes on Youtube and Daily Motion. I'll have Goro Miyazaki's film online as soon as it's available.

Heartfelt thanks to GhibliWorld for breaking the news to the English-speaking world.

2009-07-30

Hakujaden - VHS Cover

I found this little gem thanks to the little miracle we call Google. Since I'm still covering Japan's first animation feature film, I'm dragging you all with me. Heh heh.

Here is a scan of the VHS release of Hakujaden. It's a somewhat sparce design, only a few characters on the front, as opposed to the movie poster that's seen on the back. What's remarkable to me is how the female lead, Bai-Niang, is given center stage. Her expression and her pose are aggressive, dominant; the boy remains in the background, passive. It's the sort of gender role reversals we're accustomed to seeing from the Studio Ghibli films.

I'm also impressed that the couple are front and center in Japanese promotions for this movie, while Panda is a supporting character. Those roles were completely switched when it was imported to the US as Panda and the Magic Serpent. The conventions of American cartoons pretty much require it. The funny thing is, I'm not sure things would change very much today.

Of course, I wouldn't complain if Hakujaden and the other classic Toei movies found their way to our shores. I'd just be thrilled to see this movie at the Mall of America Best Buy. Heck, I'll be happy if Ghibli Freaks everywhere download the fansub and watch it. This is where I should seriously pursue the idea of panel discussions at anime conventions.

Hakujaden - Correct Screen Ratio?

Ghibli Freak Joshua sent me these two screenshots from Toei Doga's landmark classic Hakujaden, in an attempt to solve a riddle that is puzzling us: what is the correct aspect ratio for this film? The Japanese DVD is presented in 4:3, while the newer French DVD is presented in 16:9. Which is correct?

I have admit that I just don't know. I've gone back and forth on this. At this point, you could convince me either way, but without hard evidence or any original sources to read, it's only guessing. I've sent a message to Ben Ettinger, and hopefully he will be able to answer. There really isn't anybody else on this hemisphere who probably could, to be honest.

This brings us back to Joshua's direct comparison between the two DVD versions. The French version is set in widescreen, but this is not a stretched picture frame. Instead, it appears to be cropped from the top and bottom, with some extra image on the sides (which lie just outside the 4:3 frame).

Take a look at these and see what you think. I must admit my ignorance on the matter. My best guess is that Hakujaden really was created in 4:3 ratio, but it does also look nice when stretched out to 1.66:1 on the media players. If anyone could find some animation cels or e-konte books, that would solve the riddle once and for all.. Good luck on that.

Poster - Panda Kopanda (France)

Buta Connection has just reported that Panda Kopanda and Panda Kopanda & the Rainy-Day Circus will be released to theaters October 14 in France. Here is the new movie poster, which looks terrific.

Panda Kopanda was created in the wake of Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki's Pipi Longstockings project was scuttled, and most of the old gang from Toei was on hand to contribute as well. The freewheeling atmosphere is clearly visable on the screen, and both Panda shorts have a peaceful, lighthearted feel that points back to Toei Doga, and forward to Heidi and, much later, My Neighbor Totoro.

Also included in the production team was a young 23-year-old Yoshifumi Kondo, who was discovered on Lupin III. He would become a crucial partner for both Miyazaki and Takahata, on Future Boy Conan, the second Lupin III series, Castle of Cagliostro, Anne of Green Gables, and Sherlock Hound. In 1984, Kondo directed the Nemo pilot, a true anime masterpiece, and later migrated to Studio Ghibli, where his success is well known.

Movie Review: Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986)

March 3 , 2004

Castle in the Sky is a heartwarming bliss-out of a movie, full of spirit and fun, and reminds you of the kind of movies Hollywood used to make long ago. Watching, I am reminded of the golden age of Hollywood romantic swashbucklers, of Errol Flynn and Saturday afternoon serials. Is it odd that today's live-action movies are increasingly becoming more and more cartoonish? That genuine spark of imagination is increasingly hard to come by, lost in a sea of plasticized computer animation. Yet here is a swashbuckling picture that’s worth its weight in popcorn.

Castle in the Sky is something of an adventure chase movie, about two children who search for a legendary city behind the clouds. Sheeta, the girl, is pursued by the army, government agents (who will remind you of the Agents from The Matrix), and a gang of pirates; she carries a jeweled family pendant that may hold the key to discovering the city, named Laputa after Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels.” Sheeta, like every Miyazaki heroine, is confident and assertive, and would sooner grab a glass bottle and knock out her captors than merely wait to be rescued.

After an assault on a zeppelin, Sheeta escapes both the agents and the pirates, and is discovered by Pazu, a wide-eyed boy who lives in a mountainside mining town. He loves to build airplanes, and dreams of adventure; he practically bursts at the seams when he’s speaking of his late father’s accidental discovery of Laputa. Like Sheeta, he is also an orphan, and becomes a kindred spirit; the blossoming romance is both eloquent and old-fashioned in that classic Hollywood way. “When you fell out of the sky, my heart was pounding,” Pazu tells her. “I knew something wonderful was about to happen.” It’s a great line.

The success of Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind enabled Miyazaki and Isao Takahata to create an independent animation studio, where they could create their own unique works. Most of the key players from the Nausicaa film were brought on board, including key animators and composer Joe Hisaishi (his score is excellent), and Studio Ghibli was born. Castle in the Sky was the first Ghibli release, and fills the requirement of a well-rounded crowd-pleaser. The tone of the film is lighter than Nausicaa, and less serious; a goofy anarchy is scattered throughout. The pirate gang is largely composed of an older woman named Dora (a dead ringer for Pipi Longstockings’ mother) and her bumbling sons, mama’s boys, all. Outlaws, yes, but disarming characters who grow on you by the end.

There is a great scene early on, where the Dora boys get into a macho boxing match with Pazu’s adoptive father. It’s a sequence of huffing and flexing and punching, and pretty soon the whole town is brawling. It’s all great screwball comedy, like something out of It’s a Mad, Mad World or Blazing Saddles. This sets up one of the most inventive chase scenes Miyazaki, or anyone, has ever filmed, involving the Dora clan, the children, and the military across a series of vertigous bridges and trains.

There are a number of thrilling chases, set squarely in the adventure serial mold, involving trains, giant robots (a tribute to Max Fleisher’s Superman cartoons), flying fortresses, gliders, and aircraft that resemble giant beetles. This is a Miyazaki film; there is a lot of flying, more than in any of his movies save Porco Rosso, and everything has a free, sweeping flair. There isn’t another filmmaker that makes flight so boldly romantic.

Throughout everything lies some wonderful animation and artwork. Castle in the Sky is a great-looking movie. You see how the creativity unleashed in Nausicaa has grown, as every succeeding Ghibli production does; you can practically see the gears turning in the filmmakers’ heads. There is an emphasis on background detail, and composition and framing, in minor touches and quieter moments where nothing much really happens.

The influence is much closer to live-action cinema than the American style, which emphasizes liquid movement and very fast cutting (the reasoning is that audiences can’t sit still for more than two seconds). One of my favorite scenes involves Pazu’s morning ritual of playing his trumpet to a collection of doves; the birds are fed when the song is done. I love this moment precisely because it has no bearing on the plot; we're simply being asked to enjoy the moment. These moments reoccur repeatedly, especially in Castle’s final third, when the floating island of Laputa is discovered and all the players come to a head.

The world of Castle in the Sky is an inventive mix of futuristic and Victorian-era technology. Pazu’s town is based on a Welsh mining town, with houses cut across giant mountain gorges, locomotives, and Model T’s. It all fits into the spirit of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, and, yes, Swift. Why does so much animation, Japanese and American, follow such dull, slavish formulas when such uncharted territory remains un-mined?

The final act becomes quite serious, with reflections on nature and war and human frailty; the scenes on Laputa are inspired, in part, by Miyazaki’s Nausicaa books, and are genuinely moving. Miyazaki is an entertainer in the grandest sense, a gentile Steven Spielberg; he’s Spielberg without the schmaltz.

Movie Review: Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind (1984)

January 8, 2004

Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind is one of the true landmarks of animated cinema. Twenty years after its release, in a time when animation evolves by leaps and bounds, it continues to offer challenging ideas and genuinely move audiences. In Japan, Nausicaa routinely places at the top, or near the top, of every poll of the best anime films (it spent ten years at the top of Animage magazine's readers' polls, for instance). Here is a science-fiction adventure with ideas, with vision and heart.

Hiyao Miyazaki made a name for himself animating and directing various movies and TV shows during the late 1960s and ‘70s, including popular shows such as Future Boy Conan and Lupin the Third. After directing his first feature film, 1979’s Castle of Cagliostro, and without any studio projects, he directed his energies on an original manga (graphic novel) saga. In 1982, Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind appeared as a monthly serial in Animage, and quickly proved so popular that demand arose for a movie. After early resistance, Miyazaki relented, on the condition that he direct the picture, and his longtime colleague Isao Takahata produce. They enlisted Topcraft Studios (best known for the Rankin-Bass version of The Hobbit), hired a skilled musician named Joe Hisaishi to compose the score, and released the film to theaters in 1984.

Based on a 12th Century Japanese folk tale (“The Princess Who Loved Insects”), Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind is set in a post-apocalyptic world where humans struggle to live amongst poisonous fungus forests, mutant insects, and herds of giant blue-eyed slugs called Ohmu. The heroine, Nausicaa, is a chieftain’s daughter, lives in a small nation in a protected valley, and shares an empathic bond with the insects of her world; she firmly believes that humans and insects can peacefully coexist, despite the ever-present threat of the growing forests. She’s the archetype of the Miyazaki heroine: strong-willed, confident, and full of spirit.

The Valley of Wind suddenly finds itself in the middle of a war between two warring nations, Torumekia and Pejitei. The combatants disrupt the relative peace of the Valley and start shoving their weight around. A God-Warrior, the ancient weapons responsible for the destruction of civilization, is unearthed. Both sides vow not only to defeat their enemy, but to burn back the forests and reclaim nature. This sets the stage for a number of action set-pieces (including some terrific aerial combat scenes), moments of quiet introspection, a fair amount of light humor, and a search (by Nausicaa) to solve the mystery of the mutated environment.

All the great hallmarks of Miyazaki are present in full: self-confident female characters, concern for the environment, solid compositions, an optimistic humanism, and lots of flying. When you look at the history of animated movies, you realize how groundbreaking Nausicaa really is. There are no song-and-dance numbers, no wise-cracking animal sidekicks, no simple-minded moral lesson for the kiddies, nothing in the traditional Disney mold. Yet, this also is not some juvenile adolescent sex fantasy ala Ralph Bakshi or Heavy Metal. Nor is this a clone of Star Wars or JRR Tolkein. This is a new style of animated film, opening the doors for movies like Waking Life and Millennium Actress and Whisper of the Heart and Princess Mononoke.

Howard Hawks once claimed that a good movie should have three great scenes and no bad ones, and Nausicaa has the pick of the litter. The first such scene is a wonderfully stylish flashback sequence involving Nausicaa as a young girl. The flashback is drawn in a hypnotic, slightly surreal movement of rough pencil sketches and minor watercolor touches. The child tries in vain to protect a baby Ohmu from faceless adults (including, importantly, her father), only to lose her pet in a swarm of clawing hands, and it’s a great moment; all those swaying hands remind me of the “Tower of Babel” sequence in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

The second great scene is a tribute to something usually overlooked in animation: the acting. It’s the moment when Nausicaa tries to rescue a young ohmu, which has been deliberately injured in order to trigger a deadly stampede. The giant insect sees the herd on the opposite side of an acid lake and starts crawling towards them. Nausicaa struggles to hold the Ohmu back, but her leg is pushed into the lake; she screams. The actress, Sumi Shimamoto (who also appeared in Castle of Cagliostro, My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke), belts out a sustained scream that chills to the bone. It’s one of those great acting moments that fans often recall in hushed tones.

The third great scene occurs thirty minutes into the picture. The Valley of Wind is invaded by the Torumekian army, and something happens. I won’t reveal what, but this incident drives Nausicaa into a fury. She grabs a weapon, yells out, and kills several guards before she is suddenly stopped. It is a sudden and violent moment; this scene is shocking, and it sears into your mind. She doesn’t merely kill the soldiers, she cuts them down.

Is this the most important scene in the film? Without it, the movie doesn’t work; it would be little more than a preachy environmental parable (“man and nature can get along”). With it, the movie suddenly becomes much more complicated, nuanced. If the hero were male, this would be an expected cliché; almost a rite of passage. How many American films see violence as the answer to all questions? The gun is usually a substitute for the questions themselves.

When you put an intelligent, almost pacifist heroine in the role, the meaning changes. This girl is just as capable, deep down, of the same impulses that drive her adversaries to kill. She’s no longer just a pure Gandhi figure who always chooses right. Nausicaa is an animated film that firmly attacks gender stereotypes. Notice how the heroine avoids the traditional Disney cliché of the helpless princess who waits to be rescued by her prince. Notice also how she avoids the anime and action movie cliché (think Charlie’s Angels) of the superbabe who kicks ass and coolly dispatches tired one-liners.

The more I watch this film, the more aware I become of how effectively Miyazaki blurs these distinctions, to create characters who are more complex and emotionally honest. Kushana, the leader of the Torumekian army, is likewise not a typical cartoon villain, but a sympathetic character. When she casually reveals that she has lost her arm to insects (and possibly both her legs), you understand why she wants to burn the forests. There are also hints of conflict with her superiors back home, if you pay close attention. There are questions raised that are not necessarily resolved.

A lot of this is because the movie was based on an ongoing comic, which had just finished two volumes. Miyazaki is still working with some of the characters, wrestling with their motivations. The manga was still a handful of open threads; the screenplay does a terrific job of streamlining everything into a two-hour movie, while still showing echoes of greater events and themes to come.

Miyazaki would spend the next ten years, between movies, writing the manga; when he finally finished in 1994, he had written seven volumes and nealy 1100 pages. The scope of the story grows far beyond the boundaries of the movie, and grapples with the deepest themes of literature. The finished Nausicaa epic is one of the greatest novels I’ve ever read, and still, the elements of that story -- the blurred lines, the pathos, the action, the characters – are visible in the 1984 film. Maybe not as vividly, but everything’s there. Notice, also, how nearly all the original events in the movie are recycled back into the novel at various points, especially in the final volume.

This is what draws me back time and again. I enjoy the movie for what it achieved, for the barriers broken, for the way all the various versions (film, novel, Mononoke) intersect. Even its flaws are compelling. That ending is practically the definition of deus ex machina, but when it works so well, does it really matter? Does it matter that later anime like Akira or Ninja Scroll have smoother animation? Those movies are cold-hearted, mean bastards. This movie pulses with life.

Why Can't We Be Friends?

On Cartoon Brew's recent Miyazaki-themed posts, I've read a surprising number of commenters cast doubt on the friendship between Miyazaki and John Lasseter. I don't know how many people believe this (the internet is notorious for exaggerating crank ideas), but I'm reading occasional opinions like this:

"I still don’t understand why Lasseter and Miyazaki get along. Miyazaki’s position seems particularly cynical."

Am I missing something here? Why is there such skepticism about the friendship between John Lasseter and Hayao Miyazaki? Where exactly is this coming from? When they first met around 1980, Miyazaki was in the States working on the Nemo movie project (before withdrawing), and he was at the low point in his career. Castle of Cagliostro, his first directoral film, was a box office failure. Sherlock Hound (Meitantai Holmes) was scuttled by Telecom after six episodes were created but never aired. His great television series, Future Boy Conan, had finished its run in 1978. In fact, Miyazaki’s great triumph was Heidi in 1974 and 3000 Leauges in Search of Mother in 1976.

Clearly, in 1980 there was no master plan to take over the film world. Miyazaki would be absent from anime entirely for the next four years, before his film version of Nausicaa signalled his triumphant comeback.

John Lasseter, likewise, would see the darkest days of his career. He would lose his job as a Disney animator, then find work with George Lucas’ obscure computer graphics company. Said company was bought by Steve Jobs, and nobody at the time could have dreamed that Pixar would become the Great American Movie Studio.

The idea that Lasseter and Miyazaki’s friendship is cynical business politics is absurd. It’s beyond absurd. What is it with Americans and stupid conspiracy theories, anyway? Are we going to ask John Lasseter for his birth certificate next?

2009-07-29

Movie Review: My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999)

March 1, 2005

Pom Poko (2006 Review)

January 26, 2006

Pom Poko is at once instantly accessable and completely foreign. Japanese culture is alien to American eyes, and Pom Poko is Takahata's celebration of that unique Asian culture. It's the most alien of all the Studio Ghibli films.

Pom Poko is, as Takahata described it, a "fictional documentary" about the culture clash between tanuki and mankind, from the tanuki point-of-view. It is a story about the animals attempts to hold back the tide of human progress, and it is also the story about an indigenous population swallowed up, taken from their own land.

This is a film that wears many hats, perhaps too many for those who look at the animals and expect Winnie the Pooh or Bambi. The story weaves through slapstick comedy, social commentary, satire, surrealism, and tragedy. It changes moods much the way the tanuki change form, bending and molding into a new shape, and relentlessly moving forward.

I think you will understand the overall plot, as the playful tanuki play endless pranks and try a variety of ideas to drive the incoming humans out of their forest. You will likely miss many, if not most, of the cultural-specific themes; the children's folk songs, the stories and antecdotes, the mythology, the religion. But don't worry too much; Takahata aims to rewaken his Japanese audience, one becoming more and more Westernized, to their vast heritage. Repeated viewings are absolutely required.

Pom Poko is a little different for Takahata, but he still employs all his talents, and his brilliant, calculating mind is very much in evidence. Thematically, it's very similar to The Story of Yanagawa Canals and Miyazaki's own Spirited Away, but with a darker, more tragic turn. It's as much a eulogy as a call to arms.

One last note for the teenagers and dumb college kids. You've heard right. The male tanuki are shown with their genitals. It's, again, purely a cultural thing. People in Japan don't have a problem with it. Get over it. Grow up.

Soundtrack notes: Disney released Pom Poko (alongside My Neighbors the Yamadas) last summer on DVD, with a new dubbed soundtrack. Unfortunately, it's pretty terrible. Not that the quality of the acting is poor (it's actually quite good in parts), but so much of the original script is scuttled or censored that it just ruins the film. I guess not everything can be whitewashed into the vapid, Stepford Family-fed Disney formula, can it? Thank goodness for that.

Movie Review: Omohide Poro Poro (Only Yesterday) (1991)

February 28, 2005

Isao Takahata is not a name most Americans will recognize. Mention his name, and more often than not, you will be greeted with shrugs. But make no mistake: Takahata is a poet who has revolutionized animation as an art form. If you see his Grave of the Fireflies, you will be tempted to call it his masterpiece. I felt the same way myself, but I was wrong. Omohide Poro Poro is his masterpiece.

I'll be even bolder and declare this to be the finest animated picture ever made; a grand achievement of animation as art form. It proves to be deeply moving, at many times overwhelming; yet is also close, small, intimate. This is one of the great movies of our lives.

Takahata only made one fantasy adventure picture, his first, The Adventure of Hols, Prince of the Sun, in 1968 with Hayao Miyazaki. Miyazaki fell in love with adventure movies; Takahata moved in the opposite direction, towards realism. He strove to create animation influenced by neo-realism, a naturalism in the style of Jean Renoir and Yasujiro Ozu.

Omohide Poro Poro best incorporates the traits and skills Takahata developed during the 1970's, when he revolutionized animation in Japan with World Masterpiece Theatre, presenting television renditions of Heidi and Anne of Green Gables, and then in 1982 with his great Goshu the Cellist.

His style is reflective and deeply personal, very much like Ozu, but Takahata's greatest gift, for me at least, is his ability to take us inside the heads of his characters as their imaginations take flight. That trait is what made his version of Anne so memorable; here, he takes one story and molds an entirely different story from within.

Omohide Poro Poro is the story of a Tokyo office worker named Taeko. At age 27, she feels dissatisfied, unhappy with her life. She slowly begins to question some of her life decisions, her choice in careers. When we first see her, she has decided to spend a week with her sister's in-laws who live out in the country.

Taeko puts on a happy face and gets along well with others, but we discover that much of this is a shell, a cover. Over the course of the movie, she wonders out loud if her whole life has been a front to pacify the outside world. Perhaps she is entering another moment of growth in her life, and she begins to reflect upon another similar time, her childhood and early adolescence.

The movie dances about, from the present day (1982) to Taeko-chan's tenth year (1966), and back again. For almost anyone's first viewing, it's the flashbacks in Poro Poro that leap out in our minds. These scenes are drawn in a style I've never seen before in an animated film. The screen is drawn very sparsly, with colors and details fading away at the edges of the screen. The amount of visual detail is striking, almost like sketches from a beloved children's book, painted with spring-tone watercolors.

The 1966 episodes capture that painterly sense of nostalgia better than just about any other movie I've seen. One obvious comparison I could make is Wild Strawberries; imagine Bergman's classic, drowned in Warhol pop, echoing song lyrics like Bob Dylan in his prime. It's a thing of beauty to watch the past and present intertwine, commenting on one another, dancing in grand celebration of the joys and sorrows of life.

How can I describe this to someone in America who only knows animation in the language of Walt Disney and Chuck Jones? Our first time watching Grave of the Fireflies is a lot like being hit in the chest with a cinder block. It's impossible not to be deeply moved, and I've discovered that Takahata achieves that feat in all his work. Fireflies, of course, has its poetic tragedy; this film affects me far more with its beauty and grace.

Looking at the life of this woman, we identify with her awkwordness and tragedies. Taeko-chan's life is a series of setbacks, losses great and small. Granted, she is on a path to her self-discovery, but it isn't until the very end that you realize the great unspoken conflict in the movie. Namely, how did this precocious, curious child become the polite woman in a stale desk job? Her story is much like the Japanese saying that the upright nail gets the hammer; it's Takahata's thinly-disguised stab at his country's conformist culture.

There are so many brilliant moments in the 1966 scenes that describing them would mean reciting the entire plot. I love the episode involving Taeko's crush on another boy in school; a baseball game is skillfully played as duel, chase, and showdown that captures all the magic and fear of first loves. I love the sequence involving the girls' emerging puberty and emergence into womanhood; it's both endearingly funny and sobering from a boy's point-of-view. I'm endlessly enamored with Taeko's short stab at acting, which leads to interest by the local college theatre group; it's a masterpiece of editing and pop montage, it turns horribly tragic, all set against the backdrop of a popular children's show called Hyokkori Hyoutan Jima. The final moment is a redemptive triumph that beautifully sums up Taeko's whole life, and maybe Takahata's, too. It may be the best scene he's ever filmed.

By contrast, Poro Poro's other half - the story set in the present - exchanges the faded pop nostalgia for luminous, bold colors, family drama, and an almost documentary realism. Taeko's arrival in the country brings her in the company of Toshio, a young man who walked away from the punishing city life for the simple life of a farmer. "Do you like this music?" he asks Taeko as he walks her to his car. "It's music for peasants. I like it because I'm a peasant, too." His cheery demenor and thoughtful disposition begin a series of conversations between the two, very often in that tiny car.

Toshio's conversion to a more traditional rural life fits in with much of the nostalgia in Studio Ghibli's films; I strongly suspect this may also be a direct conversation with the audience. By 1991, Japan's bubble economy had burst, plunging the nation into a cycle of endless recession that only now is ending. Takahata (who doesn't quite share Hayao Miyazaki's legendary work ethic) has little respect for the unrelenting corporate culture. His world resides in the quieter, rural Japan of the past.

This life is neither shown to be light or trivial; it is hard work at long hours and little pay. A brilliantly moving sequence goes into great detail showing the process of picking safflowers to make cosmetic dyes, and then brings us to the fields at dawn as Taeko and her relatives pick flowers. Now maybe I was mistaken before; maybe this is the greatest scene Takahata has ever filmed.

This moment is so sparse, so perfectly zen, that we almost think we're watching nothing at all. But watch them pick flowers. Listen to that majestic Hungarian folk and choir music - such marvelous music! - and just wait, enjoy the moment. Gradually, slowly, almost in real-time, we see the sun peak behind the mountains, and it dawns on us: we're watching the sunrise. It's just about the most beautiful scene I've ever witnessed.

When you look at Isao Takahata's greatest works, you find a crucial common denominator: Yoshifumi Kondo. Kondo served as the charcter designer and animation director on Anne of Green Gables, a role he reprised faithfully for years at Studio Ghibli. His drawing style is superb, absolutely perfect for a naturalist style. His sensibility is also close to Takahata's, who later remarked that both Grave of the Firefles and Poro Poro could never be made without him. I say Kondo was the best character artist in the business, and his death in 1998 remains a terrible loss.

The official western title to this film is "Only Yesterday," although I confess I much prefer the original Japanese title, "Omohide Poro Poro" It can be (loosely) translated as "Memories of Falling Teardrops," which appeals to me because of its Yasujiro Ozu influence. It seems fitting to me that both Japanese filmmakers should be mentioned in the same breath. This film is a work of genius - Ozu painted with watercolors.

---------------------------------

(Update 11/24/12: I've been asked to clarify on the movie's title. "Omohide Poro Poro" doesn't have a direct English translation. "Omohide" means "memories," and "Poro Poro" is a Japanese onomatopoeia that, in this instance, carries a double meaning: "raindrops" and "teardrops." This is similar to the double meaning in Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies - "Hotaru no Haka" doubly suggests fireflies and firebombs. In any event, "Memories of Falling Teardrops" is a slightly poetic translation of the Japanese title, and it's suggestive of Yasujiro Ozu's movies. You may prefer a slightly different translation. In any case, I always refer to this movie in its original Japanese title, Omohide Poro Poro. And, no, I've never been a fan of Ghibli's "international" titles; the original titles are much more poetic. Don't you agree?)

Movie Review: Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

January 20, 2003

When the American movie-going public is constantly being fed junk food, it ruins their sensibilities. They don't trust their better instincts. Whenever I tell anyone who will listen that Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies is just about the greatest animated picture ever made, I'm greeted with strange looks. Nobody really believes that. American animation mostly relies upon formulaic pastry ala Disney, Dreamworks, and television. But Fireflies is far different; a transcendent masterpiece in its own right.

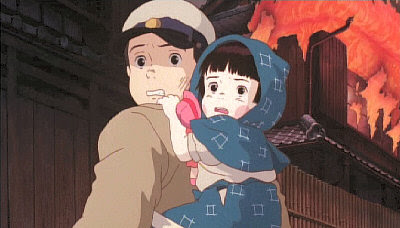

It's hard to get someone fired up about a picture that's so hard for Westerners to define. At the core, Grave of the Fireflies is a movie about two children who are bombed out of their home during World War II. Not exactly the way to reach someone who just dumped Shrek in front of their kids.

Fireflies is certainly one of the more serious Studio Ghibli titles, and one can't imagine any other studio that would produce this movie and My Neighbor Totoro at the same time. The two are nearly polar opposites (and shared a double bill for its Japenese premier), but its that creative diversity that has made Ghibli the best movie studio in the world.

The story is based on a bestselling novel by Akiyuki Nosaka. A survivor of the firebombing of Kobe in World War II, Nosaka battled starvation and actually lost his younger sister to malnutrition. Haunted for years by the experience, driven by the guilt of his sister's death, he wrote the book in hopes of silencing the ghosts surrounding him.

Like the book, the movie focuses almost exclusively on two children who become casualties in the Kobe bombing. All throughout, there is an encroaching sense of isolation. Seita and Setsuko lose their home, then lose their mother. They travel to the home of a distant aunt, who turns out to be distant in more ways than one. Increasingly frustrated, the aunt coldly discards the children; they lose their surrogate home and turn to a hillside bomb shelter. The surrounding adults, the farmers and the doctors and the officers, are either unable or unwilling to notice the orphaned two. The world itself seems to be collapsing around them.

Grave of the Fireflies is such an emotional experience that it's difficult, nearly impossible for many, to make it through in one sitting. Take one pivotal scene, for instance. The children's aunt is persuading Seita to give up his mother's garments so they can be sold. Setsuko awakens to see her aunt taking the clothes, and starts screaming; she comes completely undone. Seita is struggling to hold her back and he's coming undone. The kicker is that the girl doesn't yet know her mother died. All the while, Seita's ghost is watching (as he silently narrates), and he's coming undone; he can't bear to hear his sister's cries.

The first time I watched Fireflies, I was so overcome at this point in the story that I had to turn the videotape off. I couldn't return until the next evening, because it's so hard to watch. Even now, several years and several vewings later, its suffering and peacefullness remain a deeply touching experience.

When speaking about this film, Takahata and Nosaka confess that this story is better suited for animation, and they may be right. Perhaps this simply couldn't work with live actors. We would be too self-conscious of the sight of a real 4-year-old suffering; it would either look overly maudlin or hokey. But when animated, we more readily accept what Takahata shows us. It's realistic, but in the sense that Van Gogh and Coltrane is real. With its warm humanity, you feel emotions pulled out of you that you never knew you had.

Fireflies is equally full of moments of serene beauty, scenes of peaceful vitality. Visually, this is a beautiful movie. Everything is drawn in lush, vivid watercolors; the greens and blues of the lake, the saturated reds of a devastated Kobe, even the smoke from the bombers looks poetic. A bucket, a mop, a well - the film is littered with these snapshots of daily details. These transitory pillow shots are straight out of Yasujiro Ozu's movies (with a couple nods to Ray's Apu Trilogy), and it's these naturalist moments that stay with me the most.

This style of filmmaking is almost unheard of in animation. In the film's signature moment, the two children fill their cave with fireflies from the lake. The look on their faces is almost rapturous joy. The fireflies are gathered, they fly around the cave. It's an almost spiritual moment; the fireflies dance and glow, then slowly dim and fade by dawn. In the morning, the little girl buries them, and imagines her own mother's death.

You can't imagine any director pulling that off in America without mangling it a dozen different ways. But after watching, how can you imagine anyone not making films like this? How can one settle for the same routine again? By the time the final credits roll, you become convinced that Takahata is a genius and revolutionary; his other masterpieces such as Omohide Poro Poro and Anne of Green Gables cement that belief.

It may take another decade or two for the masses in America to realize this, and that may not happen until some brave filmmakers finally try to create neo-realist animation here. The prohibitive costs of creating animated films and the corporate mindset of Hollywood guarantee that this won't happen anytime soon. That needs to change, because we deserve scores of movies influenced by Takahata and Grave of the Fireflies.

Site Update: My Old Essays

I think reading these will prove helpful for everyone, because it shows me in the process of discovering, learning, and absorbing these great films. Like most of you, I began fairly recently, with Mononoke and Spirited Away, then I watched old videotapes of Totoro and Kiki, and then mustered up the courage for Grave of the Fireflies (it took me two days to make it to the end, I was so overwhelmed). And around 2000-2001 I started tracking down the Miyazaki movies via Kazaa. Remember Kazaa?

My understanding of Miyazaki and Takahata was constantly evolving, just as my writing was evolving. I'd like to believe I'm a stronger writer today, in 2009. I think I was a better writer in 2005 than in 2003, when I was really struggling with long-form reviews. These things become easier over time. You just have to put in the practice time, like anything else.

So, anyway, I'll be posting my old reviews here on the blog. The original date will be included, so that there's no confusion. It should be interesting to see where my ideas have changed on these films.

Puss in Boots, Animal Treasure Island - Buy These DVDs!

I was checking my archives and realized, to my surprise, that I haven't promoted or pushed these two movie lately. So here's the hard sell once again, Ghibli Freaks: Buy These DVDs!

Puss in Boots and Animal Treasure Island are two of my favorite films from Toei, blazing fast, brilliant designs, hysterically funny. These films come at the absolute peak or performance for our beloved Toei crew - Yasuo Otsuka, Hayao Miyazaki, Akemi Ota, Reiko Okuyama, Yoichi Kotabe, Yasuji Mori, Akira Daikuhara. I don't think they were ever as perfect a unit as during this period, which began with the long, difficult struggle to realize Isao Takahata's revolution with Horus, Prince of the Sun, then cutting loose in a flurry of cheery anarchy with Puss in Boots, Animal Treasure Island, and Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves.

Two action/comedy setpieces - the castle chase in Puss in Boots, the pirate battle in Animal Treasure Island - rank among the anime classics; the elements of action, suspense, and slapstick goofiness have no peer. These should be required study for all aspiring animators.

These DVDs were released in the US a few years ago by Discotek (they also released Toei's excellent 1979 film Taro the Dragon Boy), and I think it's safe to say they've all but disappeared. A crying shame, because these are wonderfully entertaining movies. Miyazaki fans should already have bought several copies to give to friends and family. At least, that's what I did.

Poster - Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves

I just love the Czech movie posters. They have such a terrific sense of abstract style about them. I discovered this poster for Toei Doga's 1971 film, Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves. It was directed by founding studio animator Akira Daikuhara, who, alongside Yasuji Mori, built the studio into an animation powerhouse. As best as I can tell, this was his final film.

After Ali Baba, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata finally made the jump to A Pro, joining the rest of the old gang on a new television show called Lupin III. This is a terrific farewell, loaded with wild colors and goofy fun. This may be the zaniest movie in Miyazaki's long career, the final hurrah to his thrilling comedy trilogy, which began with 1969's Puss in Boots and 1971's Animal Treasure Island.

I found this poster on this site. It's not for sale, but you can browse through the very large and impressive catalog.

Hakujaden - Japanese and French DVDs

First, here is the Japanese DVD. All of the classic Toei Doga films were released on DVD around the year 2000 in Japan. The cover features the movie poster, which is quite nice. I always have a thing for Asian movie posters; they're always so densely packed works of montage art. Hakujaden features an elegant design, the title centered on the page, seperating the two lovers. The other major characters appear on the bottom, and we even see Panda riding on the Dragon sculpture - one of the film's great moments.

As for the downsides, there are many. There are no extras, save the trailer. There are no subtitle tracks. The disc is single-layer, resulting in darker, muddier, grungier picture quality. And then there's the aspect ratio. Hakujaden is presented in a traditional 4:3 ratio, but a number of sources, from IMDB to the French DVD, suggest the correct picture frame is 1.66:1 widescreen.

The discussion thread from this post (Hakujaden screenshots) brings up this topic. I'm inclined to agree with this reader's sentiments:

"The aspect ratio for the two releases is different. IMDB says the original aspect ratio for the film was 1.66:1, which is what the French DVD has framed inside anamorphic 16:9. The [Region-2 Japan] has a fullscreen 4:3 aspect ratio. If the [Original Aspect Ratio] really was 1.66, it means that the film was originally produced in fullscreen, but matted to 1.66 when projected in theaters. In any case, the French DVD is missing some image at the top and bottom, and the Japanese DVD is missing some image on the left and right."

After tinkering around with the fansub on my VLC player, it does appear to me that the 4:3 ratio is cramped and tall. When stretched to 16:9 ratio, the picture appears more balanced, but perhaps a bit too wide. I do wish 1.66:1 was an option for VLC so I could judge for certain, but this in fact a common occurance for many movies. The 35mm film will be set to a 4:3 ration, and then properly stretched out by the projector camera. It's not a common practice for animation films (far easier to just draw in paint in the correct size), but we must remember that Hakujaden was Toei's first animation feature. So it would appear that this practice was very quickly abandoned.

In any event, it's very obvious that Hakujaden, like all the Toei Doga classics, is in need of a proper restoration and reissue. Perhaps these issues will be resolved on Blu-Ray.

Now let's take a look at the French DVD. This is a very recent release, from 2008. The title, Le Serpent Blanc, is a translation from the original title; "Hakujaden" means "Legend of the White Serpent." Thank goodness they chose to ignore the American dub title, "Panda and the Magic Serpent," but the French DVD companies have shown a remarkable respect for the Toei classics as well as the films of Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki ("Horus, Prince du Soleil").

Wild Side has previously released Chie the Brat and Horus, Prince of the Sun in France, and they've done an excellent job with both. Extensive interviews with Yoichi Kotabe and Isao Takahata were conducted for those two seminal films, and footage of their impressions of Hakujaden appear here. This may seem strange, since Toei Doga's first film came in 1958, before Takahata or Kotabe joined the studio, but it's great to hear their insights.

Also included on the French DVD is a 26-minute documentary, a 24-page booklet, and a host of other features. Wild Side has really done an excellent job. I'll leave it for you to decide whether or not the cover design works. It is very modern, I'll give it that, but when did DVD covers become so cliched? And have you noticed how Hayao Miyazaki gets name-dropped on the back? Heh heh... buy this movie, because a 17-year-old high school student who one day becomes world famous liked it! Heh heh....funny.

The picture frame is set to 16:9 widescreen, and by the few screenshots that I've seen, it does appear that part of the top and bottom are cut out. This movie seriously needs to be restored to its proper aspect ratio. But I don't expect anybody to complain. This is an excellent package and Wild Side should be proud. My only beef - obviously - is the lack of English subtitles.

I am greatly impressed that Hakujaden was finally released outside of Japan. Perhaps the rest of the studio catalog will make their way Westward. Horus, Puss in Boots, and Animal Treasure Island are already available in many regions. I'm still patiently waiting for the others, especially Little Prince and the 8-Headed Dragon, and especially Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves. And, obviously, I'd love to see everything released here in the States.

2009-07-28

"These Days, I Just Walk Around My House"

Edit 8:45 pm - I was told that this is actually Saturday's event at UC Berkely, not Friday's Comic Con. An even better scoop for us, since there's no news on Saturday's Miyazaki appearance.)

Writer and longtime Ghibl Freak Michael Burns attended the Miyazaki/Lasseter conference at Saturday's UC Berkely event, and he shares his thoughts with us, including a couple antecdotes that I haven't read elsewhere (I'm still searching for a complete video). Here is Michael's report via email.....

"I wrote to you awhile back regarding your comments on American culture. I still check your blog on a regular basis...it's simply the best thing out there when I slip into Ghibli mode.

"I wanted to let you know I was extremely fortunate to be able to attend a discussion at UC Berkeley last night with Miyazaki-san himself. When he walked into the room, the entire auditorium stood up as one and gave one of the most rousing rounds of applause I've ever heard. Miyazaki-san, perhaps a bit facetiously, broke into applause himself, before finally motioning for us all to sit down.

"The discussion covered many topics, such as the portrayal in Miyazaki-san's films of a desire to oneday see the balance between nature and mankind restored, the dangers of virtual worlds (which, Miyazaki-san admitted, have been around long before video games), the ambiguous, whimsical nature of the portrayal of animals in his films, the cultural dangers inherent in Japan's animators relying on Chinese and Korean labor, and the unfortunate fact that the current government in Japan relies so heavily on its soft power (i.e., its reliance on the export of software, i.e. anime and manga) to attract foreigners.

"Of course much (if not all) of this has been discussed before and can be found in various interviews with Miyazaki-san published online and in print. What really made the evening special was being able to observe many of the personality traits and dark humor of a man who, for so many of us, can seem, at times, more than a man.

"On many occasions during which a questioned seemed to irritate Miyazaki-san, he would utter a long, low grumble at the back of his throat before answering the question. At other times he was so taken with his own twisted sense of humor that he'd have to lean almost into the shoulder of the interviewer to stop himself from laughing. My friends, girlfriend and I were very taken by him. The conversation made me nostalgic for the grandfather I never had.

"In any case, I thought you'd enjoy a quick report. I'm incredibly thankful for aicn for posting the information about this event, but if anyone ends up posting this, I'd rather it be you than them. Your fandom is obvious, and you deserve the scoop. I'll leave you with some choice moments from the evening:

"Miyazaki-san at one point admitted that he hoped he could see the end of human civilization in his lifetime. Later he admitted that, sometimes, when standing in high-rise buildings in Tokyo, he likes to imagine the sea sweeping most of the buildings away as he watches from above.

"Also on the topic of floods, he discussed the regular flooding he and his wife experience in their small-town home. He said that when heavy rains bring floods, the water only goes up as high as peoples' knees, and since it doesn't pose all that big of a threat, old people begin to come out of their homes, play in the water, help eachother, and just generally be happy together in brotherhood with their neighbors. He admitted that, though they have the means to build their home higher to avoid the water completely, he and his wife have decided to leave things as they are, so they can experience the floods along with their neighbors.

"Finally, when one of the audience members posed the question "is there a specific place you like to travel to for inspiration?", Miyazaki-san replied humbly, 'These days, I just walk around my house.' "